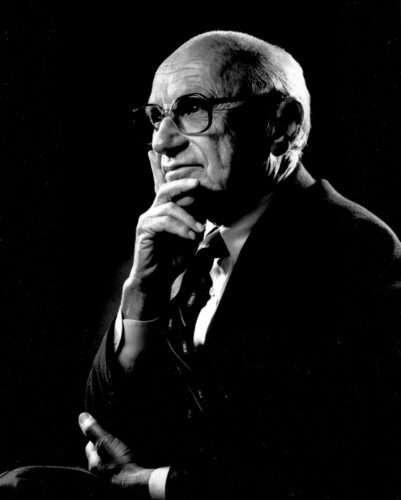

Decades ago, Milton Friedman explained that monetary policy impacts the economy with long and unpredictable delays. Recent reports indicate that the effects of the monetary tightening in 2022-23 are starting to wane.

Both inflation and economic growth are slowing down. In June, consumer prices dropped by 0.1%, the biggest monthly decrease since the early COVID days. While this was largely due to lower energy prices, “core” consumer prices, which exclude food and energy, rose only 0.1%, the smallest increase in over three years. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) was up 3.0% from last June, but this year-on-year increase appears to be slowing further in July and August, especially with declining oil prices.

Economic softness is becoming more evident. The housing sector continues to struggle with slow construction and sales. The value of new private housing construction has declined over the past three months, and existing home sales are near their lowest levels since the 2010 housing bust. New home sales are also below pre-COVID levels.

The national ISM Manufacturing index fell to 46.8 in July, indicating contraction. This figure was below all forecasts and the critical 50 mark. The production component of the index also fell to 45.9, the lowest since the COVID lockdowns.

July’s employment report showed a significant slowdown in job creation, with a net gain of just 85,000 jobs after accounting for downward revisions from previous months. Excluding government jobs, education and health services, and leisure and hospitality, the “core” measure of payrolls increased by only 17,000, the smallest rise this year. The unemployment rate rose to 4.3%, up 0.4 percentage points from three months ago, a rise that has often, but not always, been associated with a recession.

Although the M2 measure of money began to rise in October, the increase has been only 2.4% annualized, much slower than the 6.1% annualized average in the twenty years before COVID, a period when the CPI rose by a moderate 2.1% per year.

With both inflation and growth slowing and a sluggish rebound in M2, it appears that the Federal Reserve has enforced a tight monetary policy. Given the delays between policy changes and their economic effects, the Fed now has the opportunity to shift to a less restrictive monetary policy.

For many analysts and investors, this means lowering the short-term target rate. As of late Sunday, the futures market for federal funds indicated nearly 125 basis points in rate cuts later this year. However, simply lowering rates does not necessarily ease monetary policy.

Instead, the Fed should focus on the money supply, particularly M2. If short-term rates are cut but money supply growth remains weak due to tighter bank capital requirements or expectations of even lower future rates, then monetary policy is not truly easing.

There’s a common misconception that 1980s Fed Chairman Paul Volcker beat inflation by sharply raising short-term interest rates. In reality, Volcker focused on controlling the money supply. He used the Fed’s open-market operations to absorb excess liquidity, which led to higher short-term rates and lower inflation. The key was less money in circulation, not the higher rates themselves.

Today’s Fed has shifted from focusing on the money supply to a system with excessive reserves, where short-term interest rates are directly controlled by the government instead of the market.

Investors have much at stake in whether the Fed gets it right. Concentrating on the money supply will be crucial in determining the Fed’s success.

Lastly, there’s a risk that the Fed could overreact. The world has become accustomed to very low interest rates and easy money. The stock market was overvalued, and unemployment was unusually low. If the Fed misinterprets these conditions as normal and adds more money than necessary, it risks creating stagflation, much like the 1970s.